Thursday, March 16, 2023

Henry

Sunday, December 18, 2022

Typhoid Merry

I almost got to be a super-spreader.

Instead, I’m isolating in my room with Bear – the first in our family to test positive for covid despite all the social distancing, masks, vaccinations, and dodged bullets.

I got covid without even noticing it. When Bear and I got home from our usual long walk Wednesday afternoon, I had an email from someone who attended the same festive gathering in Vancouver on Sunday. After feeling a little under weather for a couple of days, he failed a home covid test. He suggested we all check our coronavirus status. Most attendees promptly reported negative results – other than an unlucky few.

I’d taken so many covid tests before. This time I squeezed four drops into the plastic well, then watched the bright red line instantly light up.

After observing so much suffering during the pandemic, my own experience with covid has been blessedly anticlimactic. I’ve had no symptoms. The kids all stayed virus-free as we finished the last week of school.

However, the December schedule is a mess. And I’m still trapped in “isolation”: staying at home except for long walks in the woods with Bear; letting the kids feed themselves as the dishes pile up; and either wearing a mask as I try to get work done at my desk, or hiding in my bedroom while Christmas music plays on an infinite loop.

Before the covid surprise, I was planning to drive back up to Vancouver on Wednesday night to attend a holiday sing-along event hosted by friends at a club downtown. According to the CDC chatbot’s calculations, Wednesday was my most infectious day.

Ironically, I’d already decided to skip the Xmas sing-along and save myself for a New Year’s trip. Instead, I told the kids I was loopy on Theraflu. I hadn’t actually taken any. I just wanted to cover up my decision to take the day off, stay home, and do edibles while pretending to be sick. Still, I’m glad I checked my email before I changed my mind about heading to the piano bar. My boisterous caroling would have contaminated numerous unsuspecting revelers with aerosolized coronavirus.

Instead I’m in isolation for ten days. Blame Canada.

|

This is what covid looks like (Xmas 2022) |

Sunday, February 27, 2022

Nurses are Fiercer than Drag Queens

As we inch towards a post-pandemic New Normal, the entire Vancouver Men’s Chorus is finally gathering to rehearse together again on Wednesday evenings. Our June show on Granville Island, “R-E-S-P-E-C-T,” will be a salute to women’s music. We started learning the same songs two years ago, before the coronavirus pandemic silenced choirs and closed the Canadian border for the first time since the War of 1812.

The week before the border closure, I was in Vancouver for VMC’s annual fundraiser “Singing Can Be a Drag.” I’ve never done drag myself. Instead, I was a volunteer usher.

In addition to avoiding high heels, prior to February 2020 I also had never lost consciousness. The last thing I remember about the drag show is the lights dimming at the beginning of the queens’ performance. I’m told I fainted and fell down the stairs backstage soon afterwards. As I wrote in “Falling Can be a Drag,” I still can't remember anything from the rest of the night, including the hot fireman who arrived to minister to me after someone called 9-1-1. (Inevitably, VMC President and uberextrovert Yogi Omar ended up with the medic’s telephone number.)

Back home in Bellingham the next day, I woke up feeling sore all over without knowing why. When I returned Yogi’s frantic “how are you feeling???” text, I discovered what happened the night before. So I drove across town to the walk-in clinic. After the nurses heard my story, they made me walk across the parking lot to the Emergency Room at Saint Joseph’s Hospital for an ECG and CT scan.

None of the tests revealed anything abnormal. My excellent physician Dr. Heuristic eventually concluded the episode was a stress-related manifestation of my disability, triggered by particularly intense emotional experiences.

A random convergence of legal, medical, family, and financial crises made the last few days my most stressful and triggering week ever.

On Wednesday I was in Vancouver on my way to chorus rehearsal when I lost consciousness for the second time in my life. However, instead of drag queens, this time I had the good or bad luck of fainting in front of a couple of nurses while visiting my brother on the spine floor at Vancouver General Hospital.

|

| Leishman Brothers: Brian (lung cancer survivor); Roger (PTSD); Warren (bald); Doug (spine cancer) |

My next younger brother Doug was diagnosed with spine cancer five years ago after back pain revealed an inoperable tumor. As the heaviest Leishman brother, Doug was defensive about failing to notice a grapefruit-sized lump in his pelvis: “They’re big bones!”

Despite many challenges, Doug is blessed with the best family in the world, marvelous medical providers, and Canada’s sane healthcare system. He was able to walk my eldest niece down the aisle at her wedding two summers ago. Since then, Doug has spent most of his time bed-ridden at home in British Columbia. This month he was airlifted to VGH for nine hours of emergency surgery after a growing neck tumor paralyzed his upper body. The surgery went well, and Doug is learning how live with a wheelchair.

Our family has observed numerous parallels and contrasts as my brother faced cancer at the same time as I was learning to live with mental illness on the other side of the border. Last Wednesday, I arrived late to visit Doug in the hospital after spending my morning writing a particularly stressful letter to the State’s lawyers in response to their continuing refusal to acknowledge that I have a disability. My stress was further exacerbated by the fact that the judge in my lawsuit against the Governor’s Office had scheduled an inevitably triggering hearing for Friday morning.

While visiting my brother’s hospital room and listening to a discussion of pain management, I became lightheaded and collapsed to the floor in front of two nurses. I thought it was just a low blood sugar moment. The nurses quickly placed me in a wheelchair and gave me apple juice. I was pale and clammy, with a slow heart rate, but still alert. Until yesterday, I’d never had an even slightly elevated blood pressure reading – I inherited my father’s high cholesterol, not my mother’s hypertension. However, one of the VGH staff said she had never before seen a blood pressure reading where both the numbers had three digits.

Other than losing consciousness in the wheelchair after they checked my vital signs, this time I remember the rest of the experience. Despite the melodramatic interruption, Doug said it was educational to watch me pass out. My sister-in-law told us I looked just like my brother when he overdoses on morphine.

There are both advantages and disadvantages to passing out in a hospital. Rather than attend chorus rehearsal, I spent Wednesday evening at Vancouver General being tested and observed.

Once I regained consciousness, one of my brother’s nurses insisted on wheeling me through a backstage maze to the ER waiting room. By the time she handed me over to the triage nurse my vital signs had all returned to normal. A technician wired me up for a quick ECG and assured me my heart looked fine.

At this point they took away my wheelchair and sent me back to the ER waiting room, where I found my efficient sister-in-law on the phone finding me a place to stay overnight. Then the nice Canadian nurses tricked us. They led me down a hall to finally get my insurance information, something that happens much earlier in the process in the States.

It could have been another triggering situation – trying to communicate about a stressful topic through a plexiglass screen while wearing masks. Fortunately, although English was not her first language, this was hardly the first time she had filled out the paperwork for an unfortunate American finding himself trapped in the province’s largest hospital.

“Trapped” is the right word. After I signed a bunch of forms without reading them, she led me alone through a new set of doors to the secret inner waiting room.

Someone politely drew a few vials of blood. I texted my sister-in-law and told her I’d been kidnapped. Then I found a chair in a waiting room filled with sniffling children, Asian grandmas, and moaning hockey players.

As I looked at my new surroundings, I took a picture of the sign above the chair directly across from me. It asked: “Do you struggle with opioid use?” Ironically, this is what the nurses were talking about in my brother’s hospital room when I fainted. As Doug says, the best thing about having cancer is that even in the middle of a fentanyl public health crisis you get as much morphine as you need. Too much, in fact.

Eventually I got a text back from my sister-in-law saying “Wrong number.” Apparently her contact information in my iPhone was out of date. Unfortunately, this was also the only phone number I’d given to the hospital staff.

Fortunately, I was finally able to reach my parents. They hadn’t answered my previous calls because they were busy driving my college freshman nephew to the ER in Bellingham. (He had a concussion. I still haven’t heard that story.) I tried to obtain my sister-in-law’s actual phone number from my mother without sounding too alarming.

As a single parent, I’ve already spent too many hours in waiting rooms with a dying iPhone battery and nothing to do, eat, write, or read. Eventually I got bored and blew up the photo I’d taken of the “Welcome to the VGH Emergency Department” poster:

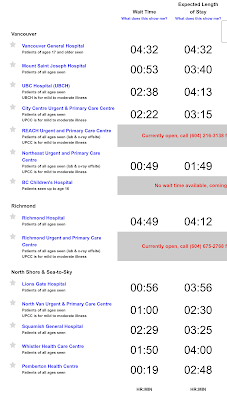

Modern technology is amazing. As directed by the poster on the wall, I clicked on the link “edwaittimes.ca” and discovered the current wait time for each emergency room in British Columbia. Unsurprisingly, Vancouver General Hospital has the largest and slowest casualty department in the province:

According to the website, I could expect to wait four hours and thirty-two minutes before getting my lab results and seeing a doctor. Perhaps coincidentally, I could expect to wait four hours and thirty-two minutes before escaping from VGH. I was almost halfway there.

Meanwhile, I hadn’t eaten for six hours. I could sense actual hypoglycemia on the horizon. VMC rehearsal was about to start without me. I was crabby. I’d left my library book, laptop, and phone charger in the car, which by now was illegally parked. My sister-in-law texted with an offer to bring me a snack from the hospital vending machines. I told her I’d been through enough triggering experiences for one Wednesday.

When I was tricked into walking across the parking lot from the Bellingham walk-in clinic to the Emergency Room two years ago, the American nurses promptly put me into a hideous hospital gown and hooked me up to a heart monitor. Armed guards surrounding the hospital campus prevented any thought of escape.

Everything is better in Canada. Despite my sister-in-law’s maternal sighs, I went AWOL. I used the last of my colorful foreign money to buy an invigorating milkshake and fries at Johnny Rocket’s. Then I moved my car to a nearby parking spot, grabbed my backpack, and snuck back into the ER treatment waiting room. No one noticed I was gone.

Drunk on chocolate milkshake and library books but completely sane and sober, eventually I decided it was time to drive home to my children.

After more than five hours had passed, I went to the nurses’ station to tell them I was invoking the Geneva Convention and returning to the States. They pulled up my chart and pointed out I hadn’t seen a doctor yet. I promised to turn myself in to my physician in Bellingham. I asked if my bloodwork had come back. The nurse said it looked fine.

After I self-helped myself to discharge from the ER, I found my way through the hospital maze back to the spine floor. My brother and sister-in-law were on the phone with my oldest niece and her wholesome BYU husband. Their baby is due this week. Last month her brother and his wholesome BYU wife passed them by producing the first great-grandchildren – identical twin boys. Despite the tragicomic plagues that beset us, my family is eternally blessed.

So far I’ve been to five Canadian province (British Columbia, Alberta, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia). How many states have I visited?

Business travel and multiple cross-country moves got me to the low forties. Then a decade ago I represented the Gay Softball World Series in a First Amendment case that involved deposing LGBT athletes across the nation. On just one trip I crossed off Arkansas, Mississippi, and Georgia. I also changed planes in Birmingham, but never left the airport. After my law school twenty-five year reunion in 2015, I rented a car and finally road tripped to Vermont, which brought me to forty-nine states. Fifty if you count Alabama.

In my first blog essay about our family’s devotion to the PeaceHealth walk-in clinic, “Dr. Practical,” this is what I presciently wrote:

I've managed to avoid hospitals for fifty-five years. In particular, as long as I retain any voluntary muscle function, I’m never going to be sick enough to go to an emergency room. Fortunately, being surrounding by loving family means that if I really needed medical assistance, someone will take me to the ER as soon as I lose consciousness. Then the ER stops being an indefensibly profligate expense.

Six months later, a gaggle of Canadian drag queens pushed me down the stairs. The next morning the nurses at the walk-in clinic tricked me into walking across the parking lot to the Emergency Room to get my heart and brain examined. At the American ER, they stripped me and tied me to a hospital bed.

This week the Canadian nurses were much nicer. Still, they were the ones who wheeled me to the ER after I lost consciousness, with my brother and sister-in-law egging them on. If that counts as “going to an emergency room,” then I’ve also been to Alabama and get to cross off all 50 states.

Thursday, February 10, 2022

SLOW DOWN MORE!!!

I don’t have any tattoos, mostly because I can’t decide between a bust of Shakespeare, my children’s names, and my longtime motto e pur si muove.

However, you may be surprised to find out I used to have a navel ring.

As part of a minor midlife crisis, I got my belly button pierced for my 35th birthday. My boyfriend at the time, Skinny Pharmacist, researched the hygiene at various local establishments and supervised the piercing process. For the next decade I hid my secret identity under a T shirt.

I had to give up my belly button ring a few years ago because of my right foot. And my children.

Have you ever had a stress fracture? They’re tiny cracks in bones caused by repetitive force, often from overuse but sometimes from structural problems. A few years ago, back when I worked for a law firm that provided Cadillac health insurance, I had a stress fracture in my left foot. I wore an awkward isolating “boot” for a month as it healed.

A few weeks later, I started to feel the same burning pain in my right foot. My Seattle doctor did two things. He sent me to a podiatrist who analyzed my feet and gait before prescribing some of the custom orthotic shoe inserts I still use. (My original inserts are held together with duct tape and relegated to my house slippers.) Because I experienced stress fractures twice in a row without noticing any particular jarring event, my doctor also ordered an MRI to find out whether I have the bone density of a little old lady.

This was the only time I’ve even been inside a fancy imaging tube. Before the technician let Magneto do his work, she made me remove my navel ring, just in case. In the excitement I left the ring behind.

Afterwards my children forbade me from buying a new one, so I let the piercing heal over. Apparently middle-aged parents with belly button rings are “gross.”

This is not a stress fracture boot. It’s a “night guard.” Not the mouth night guard that used to ease the impact of grinding my teeth, before Buster chewed it. Instead, this is the foot night guard I bought last year after my Bellingham physician Dr. Heuristic diagnosed me with “plantar fasciitis.” Your plantar fascia is the tendon on the bottom of your feet connecting your heel and toes. You know you have plantar fasciitis if the heel pain is at its excruciating worst first thing in the morning when you step out of bed, after your tendon curls up overnight.

It takes a few miles walking with Bear every day to keep both of us “functional.” Fortunately, with expert guidance from both Dr. Heuristic and the earnest folks at Fairhaven Runners & Walkers, I gradually learned to pace our walks and recover an effective equilibrium. Recently I’ve only needed to wear my plantar fasciitis night guard once or twice a week, on the days when Bear cons me into walking more than ten miles.

A couple of weeks ago, I started feeling a familiar burning in my right foot. I recognized the signs of another stress fracture, but I wondered whether it was merely part of life with plantar fasciitis. Last Friday while the kids were at school I walked into our excellent PeaceHealth same-day clinic to find out.

On this visit, I didn’t see our usual urgent care physician Dr. Practical. Instead, after having my foot X-rayed upstairs, I met with “Dr. Frank.” He tends to be the most candid of my healthcare providers. Dr. Frank immediately diagnosed a stress fracture, even though it didn’t show up on the X-rays. (They never do.)

Dr. Frank is also a power walker, so we sat and commiserated about chronic foot problems. Obviously my big question was how long Bear and I would be off the trails and stuck on the injured reserved list. Dr. Frank said his 17-year-old daughter recently suffered a similar stress fracture. (My daughter Eleanor was at the basketball game where it happened.) Dr. Frank said his daughter’s foot was already better after resting for only a week.

At this point Dr. Frank got up from our tete-a-tete and walked over the computer station, muttering the words “fifty-seven-year-old man” under his breath. He grabbed the after-visit summary for “Foot Stress Fracture” from the printer. It said Bear and I should expect to forego long walks for six to eight weeks.

As I wrote this week in “SLOW DOWN!!!,” lately I’ve made huge progress in learning how to slow down my writing and thinking processes. Finding the right pace helps accommodate the various limitations that PTSD and other stressors place on my Executive Function. Regular walks with Bear have become essential to achieving equilibrium.

“Slow down” was supposed to be a metaphor. Living with a stress fracture already is a literal catastrophe. For example, because I can’t hop away from the computer often enough, I already feel twinges of karpal tunnel and tennis elbow. Driving with a boot can be awkward. Bear is miserable. Hideous typos slip through the editing process. Life is a disaster.

Our family has compensated in other ways. I’m getting more hugs. The kids are doing more dishes. I meditate longer. My stack of library books rivals my mother’s. Yesterday I crossed the border for my first in-person Vancouver Men’s Chorus rehearsal of the year. I’m rocking Wordle. I bingewatch affirming television shows, starting with The Good Place and Ted Lasso.

Somehow we’ll make it to spring.

|

| Ursula Kroeger LeGuin (1935 - 2018) |

Growing up, Ursula K. Leguin was always one of my favorite authors. Her slowly evolving Earthsea saga remains one of my literary touchstones. In recent years I’ve also read LeGuin’s works about the writing craft itself. She is an elegant and observant essayist.

LeGuin shared her daily routine during a 1988 interview:

5:30 a.m.—wake up and lie there and think.

6:15 a.m.—get up and eat breakfast (lots).

7:15 a.m—get to work writing, writing, writing.

Noon—lunch.

1:00-3:00 p.m. —reading, music.

3:00-5:00 p.m. —correspondence, maybe house cleaning.

5:00-8:00 p.m. —make dinner and eat it.

After 8:00 p.m. —I tend to be very stupid and we won’t talk about this.

I highlighted the first item in her schedule. A writer’s life requires opportunities for sustained attention, away from the temptation of a keyboard or pen. Although walking with Bear has proven most effective for me, I’m similarly productive during the drive to Vancouver, or sitting at the beach.

Later in my day, “lie there and think” would equal sleep. Fortunately, like LeGuin, I find inspiration in the early morning.

Currently I’m learning how to sleep late enough to get all my work done. I can get plenty of tips from my children, who are experts at sleeping in.

Ursula K. LeGuin’s advice comes with a bonus. Although Bear is charming and friendly, he is also an introvert – just like everyone else in the household except for Eleanor. Bear is too self-absorbed, fidgety, and passive-aggressive to spend the night with me. [Ed. Note: Bear says it’s because he hates to listen to snoring and podcasts.]

However, it turns out Bear loves to crawl in bed for morning cuddles.

Tuesday, January 4, 2022

Another Do-Over Year

The literal translation of the Korean equivalent to “Happy New Year” is “May you receive many blessings in 2022.”

Hopefully a few new blessings.

2021 turned out to be another year spent indoors waiting for viruses, lawyers, and judges to finish their work. I didn’t see enough movies to generate a list of favorite films. The only play I saw indoors was a high school production of Macbeth (Eleanor was one of the witches). My only other non-Zoom experience was seeing David Sedaris at the Mount Baker Theatre in September.

Fortunately, one of the benefits of emerging from the fog of mental illness is that I’m reading again. In addition to magazines and other online reading, last year I finished sixty books. Here are my favourites:

Roger's Favourite Books of 2021

1. Barbara Blatchley, What are the Chances? Why We Believe in Luck

2. Vladimir Nabokov, Speak, Memory

3. Lauren Hough, Leaving Isn’t the Hardest Thing

4. Lacy Crawford, Notes on a Silencing

5. Temple Grandin, Animals Make Us Human

6. Sarah Schulman, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York 1987-93

7. Stephen King, On Writing

8. Oliver Sacks, On the Move

9. Douwe Draaisma, Why Life Speeds Up As You Get Older: How Memory Shapes Our Past

10. B.J. Fogg, Tiny Habits

11. Daniel J. Levitin, This is Your Brain on Music

12. Leslie Jamison, The Empathy Exams

13. Maria Konnikova, The Biggest Bluff: How I Learned to Pay Attention, Master Myself, and Win

14. Brian Greene, Until the End of Time

15. Michael Shermer, The Believing Brain

16. Leonard Mlodinow, The Drunkard’s Walk: How Randomness Rules our Lives

17. Eric Garcia, We’re Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation

18. Sam Quinones, The Least of Us: True Tales of America and Hope in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth

19. David Sedaris, A Carnival of Snackery: Diaries (2003-2020)

20. Simon Garfield, Dog’s Best Friend

21. Anne Lamott, Bird By Bird

22. Michael J. Fox, No Time Like the Future

23. Julia Glass, A House Among the Trees

24. Kevin Kwan, Crazy Rich Asians

25. Oliver Sacks, Hallucinations

26. Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, & Cass Sunstein, Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment

27. Alan Cumming, Baggage

28. Ethan Kross, Chatter: The Voice in Our Head, Why it Matters, and How to Harness It

29. Daniel J. Levitin, The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload

30. Stephen Hawking & Leonard Mlodinow, The Grand Design

I’m fascinated by memoirs, both as a reader and a writer. My 2021 reading list included memoirs by writers, mathematicians, neurologists, addicts, and actors, as well as dispatches from across the Autism Spectrum. Plus Vladimir Nabokov. Many English Majors identify Speak, Memory as the best-written memoir ever. It’s true – the rest of us should probably just give up writing. But we can’t help ourselves.

Upcoming blog essays respond to the two memoirs that spoke most directly to me in 2021. Lacy Crawford is a journalist. In Notes on a Silencing, Crawford describes her trauma as a sexual assault victim at a prestigious boarding school, and her triggers and re-traumas three decades later as she observed how the legal system worked to protect her abusers and their enablers.

Lauren Hough is a middle-aged lesbian writer/cable installer whose parents raised her in a weird sex cult named “The Children of God.” Leaving Isn’t the Hardest Thing tells how Hough escaped her religious roots by finding a new community in the military – only to find herself betrayed by authoritarian abusers in the era of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” It turns out Pharisees and lawyers are everywhere.

As usual, many of the other books on my 2021 reading list are about how thinking does and doesn't work.

Other than our extraordinary brains, humans are unremarkable as a species. Many animals are faster and stronger, with superior powers of vision and hearing, or superpowers like flight and invisibility. Instead, after our primate ancestors diverged from their chimpanzee cousins, evolution spent the next sixteen million years focused on building bigger and fancier human brains. This turned out to be a great longterm investment – eventually.

In the meantime, we spent most of the Pliocene and Pleistocene eons as feeble hairless bipeds cowering in trees and caves. Even after the arrival of modern Homo sapiens half a million years ago, we lived for hundreds of thousands of years scattered in small bands of hunter-gatherers, well down the food chain from more impressive predators. Even within genus Homo, H. sapiens isn't very special. To the contrary, just 100,000 years ago we were one of at least six extant human species. Even after we tamed fire and invented a few stone tools, the investment in big brains was hardly paying dividends. As Yuval Noah Harari points out,

We assume that a large brain, the use of tools, superior learning abilities and complex social structures are huge advantages. But humans enjoyed all of these advantages for a full two million years during which they remained weak and marginal creatures.

Then, just a few thousand years ago, something clicked in the human brain. Suddenly we experienced an accelerating series of revolutions: agriculture, writing, civilization, empires, industry, automobiles, and iPhones. In a cosmic blink of the eye, humans achieved supremacy over every other species on the planet.

Since this Cognitive Revolution, there hasn’t been enough time for natural selection to accomplish further genetic evolution. Instead, our enhanced human brains are responsible for the havoc wrought by the immense cultural evolution that continues at an ever-accelerating pace. At our current rate of “progress,” we’ll only need a few centuries or even mere decades before we join Tyrannosaurus Rex and the dodo in extinction, no doubt dragging the rest of the biosphere with us. Unless we finally learn how to think clearly.

For decades, evolutionary biologists and child psychologists have been trying to figure out when the human mind originated. Both point to the same breakthrough in the development of the human species and in the development of each human individual child: “Theory of Mind.”

The phrase “Theory of Mind” comes from an influential 1978 paper by David Premack and Guy Woodruff, “Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind?” Only modern Homo sapiens has demonstrated the capacity to understand our experience and to act based on the proposition that other individuals possess a mental state that may differ from our own. When humans finally evolved enough to feel empathy, our brains grow three sizes. Not just our hearts.

Some neuroscientists and philosophers focus on another important aspect of Theory of Mind: because each individual’s mental state is independent of the real world, humans can feel, believe, and foresee things that are not true and may never be. According to Harari, “large numbers of strangers can cooperate successfully by believing in common myths.”

One of the few TV shows I binge-watched in 2021 was The Wheel of Time, a sorta-feminist variation on Game of Thrones set in a fantasy world that resets itself every few thousand years. Human experience In the real world is profoundly cyclical, whether you focus on days, months, seasons, years, or the school calendar.

Last year I read several excellent books about how our brains process probabilities, choices, disappointment, and uncertainty. My upcoming blog essay “How Lucky Can You Get?” dives into these topics, including some of the insights from my favourite book of the year, What are the Chances? Why We Believe in Luck, by neuroscientist Barbara Blatchley.

Blatchley identifies our reliance on “counterfactuals” as another important aspect of Theory of Mind:

Counterfactuals are alternatives to reality that we generate, particularly after negative events. An upward counterfactual is an imagined alternative to reality that is better than what actually happened. A downward counterfactual is an alternative that is worse than reality. Researchers have found that upward counterfactuals might help us prepare to encounter this negative situation again in the future and perhaps to do better the next time.

What are the Chances? resonated with the best book I read in 2019, Carol Dweck’s Mindset. Dweck is the psychologist who coined the terms “fixed” and “growth” mindsets:

In a fixed mindset students believe their basic abilities, their intelligence, their talents, are just fixed traits. They have a certain amount and that’s that, and then their goal becomes to look smart all the time and never look dumb. In a growth mindset students understand that their talents and abilities can be developed through effort, good teaching and persistence. They don’t necessarily think everyone’s the same or anyone can be Einstein, but they believe everyone can get smarter if they work at it.

Similarly, Blatchley observes “When lucky people are unlucky – when something unwanted or awful happens – they learn from their mistakes, incorporating that experience into their expectations about the future. They are able to use their transformed expectations to change their bad luck into good for the next time.” Life becomes an upward spiral.

Somehow we all made it through 2020 and 2021, endured Donald Trump and Zoom school, and survived forest fires and floods. Now it’s another new year. The holiday snow is melting and the days already feel longer. As we slouch toward Groundhog’s Day, remember the lesson of the classic 80s movie: Bill Murray learned how to learn from experience.

According to Barbara Blatchley in What are the Chances?,

Luck is the way you face the randomness in the world. If we are open to it, accepting, not anxious or afraid, willing to learn from mistakes and to change a losing game, we can benefit from randomness. We can gain a modicum of control over this aspect of life, even if we can't control the universe on a large scale. Randomness will happen no matter what we do—chaos theory rules in our universe. Knowing how to roll with the punches; now that's lucky.