Last month both my mother and my daughter pointed out I was snapping my fingers as I talked. I hadn’t noticed.

Finger-snapping is a new addition to my repertoire of compulsive body tics. My right hand can snap pretty well, but because of my deformed thumbs it takes a few snaps to get my feeble left hand going – like a Boy Scout trying to start a fire in the rain.

The snapping started this fall, when lawyers for the State and its investigators began making particularly triggering new arguments. In the past, their lies merely caused me to compulsively leap out of my chair and pace ten or twenty laps around the house, grinding my teeth and rubbing my scalp raw. Now when I pace I sometimes trace circles in the air with my snapping right hand. So far it’s happened in response to gaslighting assertions by four attorneys of widely varying skill but narrowly varying morals. I look like I’m casting a spell to ward off evil.

I recently wrote in “Stereotypos” about how our brains and our motor functions sometimes get their wires crossed. In Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain, Dr. Oliver Sacks described professional musicians with Tourette’s Syndrome who harness the energy fueling their tics and direct it toward their creativity. The next Sacks book I read was An Anthropologist on Mars, a collection of seven paradoxical tales of neurological disorder and creativity, including various savant artists as well as autistic animal husbandry expert Temple Grandin. One of Sack’s subjects is a successful surgeon with a private pilot’s license and severe Tourette’s Syndrome. Coincidentally, I read this paragraph about Dr. Bennett shortly after I observed my own finger-snapping phenomenon:

Another expression of his Tourette’s – very different from the sudden impulsive or compulsive touching – is a slow, almost sensuous pressing of the foot to mark out a circle in the ground all around him. “It seems to me almost instinctual,” he said when I asked him about it. “Like a dog marking its territory. I feel it in my bones. I think it is something primal, prehuman – maybe something that all of us, without knowing it, have in us. But Tourette's ‘releases’ these primitive behaviors.”

|

| Not a picture of me - my thumbs don't bend that way |

In November I attended my first post-Covid in-person meeting at school. In the years since the last meeting, the topic “Learning Strategies” had been renamed “Executive Function.” Brain science is everywhere.

According to Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child, “Executive function and self-regulation skills are the mental processes that enable us to plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks successfully. Just as an air traffic control system at a busy airport safely manages the arrivals and departures of many aircraft on multiple runways, the brain needs this skill set to filter distractions, prioritize tasks, set and achieve goals, and control impulses.”

Nine months of gestation is not enough time to bake a human brain. Key functions like language and Theory of Mind take a few more years to develop. And as any neuroscientist or parent of teenagers can tell you, Executive Function is the last part of the brain to finish baking, hopefully by your early 20s.

As I explained in “7-Eleven Law School is accredited,” every three years lawyers in Washington have to report they’ve attended 45 hours of Continuing Legal Education. Each month the state bar association offers a free lunchtime webinar. Brain science really is everywhere – in November our topic was “Productivity and ADHD in Law: Actionable strategies for overcoming intense productivity demands and finding balance”:

With billable hours, meeting deadlines, compliance requirements, documentation, and stressful communication, attorneys face intense productivity demands every day. Many attorneys are also struggling with some type of executive function challenge: focusing, staying on task, organizing, managing time effectively, starting and finishing tasks, keeping a schedule, communicating with others, and more. Attorneys with ADHD and other forms of neurodiversity may have additional obstacles related to executive function.

The good news is that there are proven strategies that individuals and teams can use to increase productivity, decrease burnout, and create inclusive workplaces. Paige Porter from The How Skills will be sharing actionable approaches that have been effective for thousands of professionals working in the legal profession and beyond.

The excellent presenter outlined a series of “strategies to help neurodiverse attorneys—or anyone experiencing Executive Function challenges—to improve the way they work.”

I don’t have Attention-Deficient / Hyperactivity Disorder. But as I listened to the presentation, I had an epiphany. The neural networks in our prefrontal cortex that give us our capacity for Executive Function were the last parts of the human brain to evolve. They are the last part of a child’s brain to develop. For the rest of our lives, Executive Function remain vulnerable to all kinds of assaults. In my case, both ordinary stressors and specific PTSD triggers easily impair my Executive Functioning.

Another term for “Executive Function” is “Attention.”

In his classic book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Nobel-laureate Danial Kahneman outlined an influential model of brain function. The “fast” and “slow” thinking in Kahneman’s title refers to the human brain’s revolutionary double processor. What Kahneman calls System 1 is the ultimate in animal brains. It’s programmed to perform tasks like initiating a fight or flight, tying shoelaces, and falling in love. System 1 “operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control.” It can conduct numerous tasks simultaneously, including monitoring events, detecting threats and opportunities, retrieving memories, making associations, and leaping to generally correct conclusions.

According to Kahneman, humanity’s big brain breakthrough occurred when evolution integrated the automatic processes of System 1 with a second mental processor that is capable of Executive Function. System 2 “allocates attention to the effortful activities that demand it, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice and concentration.” System 2 is very powerful, but it has limited capacity and rapidly depletes energy.

I’ve learned to reduce the impact of my compulsive tics by distracting my hands with soothing fidget toys. It turns out I get the best results with promotional sample cuttings from the innards of Purple® mattresses. Whenever anyone in our family drives through Lynnwood, they drop by the Purple store in Alderwood Mall to pick up more samples.

After my mother observed me compulsively snapping my fingers, she sighed and went upstairs to her secret stash of purple unfuzzy things. (Some people interpret sighs as “No you can't have another one.” I hear “I love you.

Still, why do I keep losing my purple fidget things? Because I can’t see them.

[Spoiler alert – don’t read any further if you want to be a test subject in the most famous psychology experiment of the last three decades.]

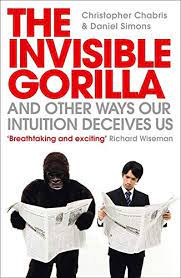

Daniel Simons of the University of Illinois and Christopher Chablis of Harvard received an igNobel award for their study design. I took their test years ago in Scotsdale, Arizona, as part of another legal education presentation. We were asked to watch a short video of two basketball teams and count the number of times a member of the white-shirted team touched the ball.

I correctly counted the number of touches. But, like a majority of test subjects, I didn’t notice the man in a gorilla suit who walked through the players while my attention was focused on counting.

Although evolution gave us uniquely powerful brains, real life often makes demands that exceed the capacity of human hardware or software. Fortunately, human intelligence learns to work around many of our biases and blind spots. For example, because of the location of the optic nerve, the visual data coming to our brains has a literal blind spot right in the middle of our visual field. The punctum caecum should always appear in front of you as a black circle bigger than the moon. But our brain’s visual systems and circuits eventually figured out a way to fill in the missing information without the rest of our brain noticing. That’s how non-Artificial Intelligence works.

I thought about the gorilla and the retinal punctum caecum blind spot last month as I struggled to tie Bear’s poop bag with one hand. Then I remembered Bear was off leash. I wondered why I was trying to tie a one-handed knot with my feeble semi-opposable left thumb.

Suddenly I saw my right hand, right there in the center of my field of vision. It was fiercely squeezing a purple unfuzzy thing.

Cognitive bias is like an optical illusion. With some illusions your vision immediately clears once you learn the secret. The gorilla video doesn’t work on me anymore.

Other kinds of blindness, like my invisible right hand holding an unfuzzy thing, or like Yanni/Laurel and the blue/gold dress, apparently will fool and divide most people forever. For these cognitive challenges we must invent compensations and circumventions, or seek accommodations.

Always remember bias is a feature of the amazing human brain, not a bug. Our “heuristics” or automated cognitive shortcuts work most of the time, from Ockham’s Razor to Hanlon’s Law to gaydar. Heuristics – biases – Kahneman’s System 1 – make it possible for our very human brains to think without blowing circuits all the time. As a consequence, the ongoing challenge for each of us is determining how much of our precious Attention we should devote to dispelling the illusions we inevitably encounter.

|

| Cognitive Bias Codex |

When I was in private practice, I often wished I’d minored in psychology. As a litigator, every client with a legal problem was also dealing with anxiety, depression, grief, or trauma. I would have benefited from a counselor’s skills.

After I was diagnosed with PTSD, I assigned myself a reading and writing list that resembles a graduate degree in psychology and neuroscience. My particular interests include how humans think and make decisions. So I was impressed this summer when the presenter during our lunchtime Continuing Legal Education webinar about effective negotiation skills included a picture of the beautiful “Cognitive Bias Codex,” and a link to its designers’ website. Someone with OCD created a taxonomy from all 182 Wikipedia entries identifying individual cognitive biases. Then a graphic designer made it pretty. The primary quadrants: (1) “Too much information”; (2) “Not enough meaning”; (3) “Need to act fast”; and (4) “What should you remember?”

When I first clicked on the Cognitive Bias Codex link, I was overwhelmed. But when I drilled down to examine the individual descriptions of fallacious reasoning, I realized I’d already figured out effective work-arounds for many common cognitive biases. I’ve written about “Hasty Generalizations” and “Begging the Question,” and faced down Codependency. Sometimes the best response to a preposterous cognitive Boggart is the incantation “Riddikulus!”

However, there’s one technique that has been proven to dispel confirmation bias: “consider the opposite,” i.e., put aside your initial conclusion and methodically list the evidence and arguments supporting the opposite result. According to Dr. Boda-Bahm, asking decision-makers “to imagine that the results pointed in the opposite direction apparently encourages them to think about how they are processing the information, and that works against the bias.”

I had the opportunity to observe the power of both confirmation bias and “considering the opposite” during a recent Zoom oral argument. We had an ice cold bench – the judge didn’t ask a single question to either lawyer. After counsel sat down, the judge announced his ruling. Although our busy trial court judge obviously hadn’t read the briefs closely, he was very prepared to dismiss my mandamus claim against the State bureaucrat who refused to file ethics claims identifying the illegal use of public resources by her own co-workers and supervisors.

The Court didn’t refer to any particular case in its ruling, only to the general rule that mandamus relief doesn’t apply to “discretionary” acts. (My Response Brief cited seven Washington cases holding that it doesn’t take “discretion” for a bureaucrat to check whether a citizen filing includes all the information explicitly required by a statute or rule; both their Motion and Reply instead cited to an inapplicable federal death penalty case).

The only statutory provision the judge mentioned wasn’t cited by either party in their briefs. It appears in a different part of the Ethics in Public Service Act, and involves what happens when the staff accepts an ethics complaint but doesn’t bother to do an investigation. Not coincidentally, in preparing for oral argument the day before I happened to have researched the entire legislative history of the sentence the judge quoted – because I know the best way to determine if you’re only seeing one side of a problem is to assume the other side’s position is correct and identify all the arguments and evidence supporting it. The statutory sentence the judge cited was the best thing I could come up in support of the State’s position, too.

One sign of cognitive bias is when you grasp at increasingly implausible motes, and ignore all the actual beams in your eye. Fortunately, when Executive Function approaches a problem with something like the scientific method – asking yourself how the evidence contradicts rather than supports your initial hypothesis – human Attention can overcome the effects of confirmation bias and other cognitive blind spots.

When I look at the Cognitive Bias Codex now, I see a beautiful flower; and a human brain; and how thinking works. It’s a snap.