At the end of July each year, my mother and her friend Carolyn spend a girls’ week at a condo in Vancouver’s West End. They watch the fireworks, shop on Granville Island, and walk along the seawall. They also attend the summer musicals at Malkin Bowl in Stanley Park, where the nonprofit Theatre Under the Stars has been producing shows since 1940.

This year TUTS presented two shows in repertory. The first, We Will Rock You, is a British jukebox musical featuring the music of Queen, with a thin plot about a dystopia where music is forbidden. The second show, Something Rotten!, opened on Broadway in 2015. Brothers Nick and Nigel Bottom struggle to find success in an Elizabethan theatre scene dominated by William Shakespeare’s rock star status. Christian Borle won the Best Supporting Actor Tony for his portrayal of Shakespeare as a preening but insecure narcissist.

|

| Seattle Men’s Chorus singing “A Musical” (2016) |

Desperate to get an edge over his rival Shakespeare, Nick Bottom offers his life savings to a soothsayer in return for learning what kind of theatrical production is guaranteed to succeed in the future. The only oracle Nick can afford is Thomas Nostradamus, an undistinguished nephew of the famous French seer. Thomas’s predictions turn out to be accurate but slightly garbled. In Something Rotten!’s show-stopping production number, Thomas convinces Nick he can succeed by introducing the world’s first musical.

In 2016, Seattle Men’s Chorus conductor Dennis Coleman retired after thirty-five years with the baton. That was also my first year in Vancouver Men’s Chorus. Instead of singing with SMC, I drove to Seattle with my daughter Eleanor to see the “Everything Broadway” show. Both of us were riveted by SMC’s performance of “A Musical.”

This summer when my mother mentioned she had tickets to Something Rotten!, Eleanor and I immediately played her the original cast recording of “A Musical,” including this classic excerpt:

THOMAS: Some musicals have no talking at all....

All of the dialogue is sung

In a very dramatic fashion.

NICK: Um, really?

THOMAS: Yes, really.

And they often stay on one note for a very long time

So when they change to a different note, [finally changing pitch] you notice.

And it’s supposed to create a dramatic effect

But mostly you just sit there asking yourself

“Why aren’t they talking?”

NICK: That sounds miserable.

THOMAS: I believe it’s pronounced Misérable.

Songwriters: Wayne Kirkpatrick / Karey Kirkpatrick

A Musical lyrics © WB Music Corp., Mad Mother Music

The key to surviving Facebook is to remember you’re not the target audience in Facebook’s business model – you’re the company’s product. Facebook’s actual customers are paying advertisers. In a popular and apt metaphor, the rest of us are merely a herd of cattle on display.

I’ve run the numbers, and I’m pretty happy with our bovine arrangement. As far as I can tell, the algorithm has never lured me into buying anything. Instead, Facebook serves as a convenient communication platform and auxiliary memory bank. After posting pictures of children, dogs, and travel for fourteen years, I can now rely on Facebook for daily reminders of happy times.

For example, according to Facebook I was at the Saint James Theatre seven years ago waiting to watch the original Broadway cast of Something Rotten!. As I wrote at the time, “Shakespeare has always been my idol.”

I’m lucky I have Facebook to remind me – because I don’t have any memory of being at the theatre in New York. In fact, other than the songs I heard on the original cast album, I didn’t remember anything about the show before I saw it again in Vancouver last month.

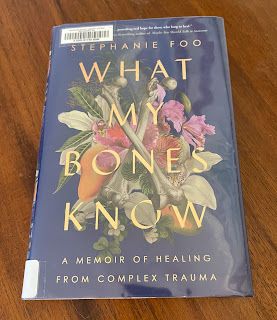

The last time I was in New York I was on my way to New Haven for my 25th year law school reunion. This was just a few weeks before my new Bellingham physician told me my weird recent symptoms added up to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and serious codependency. My disability diagnosis changed my life – but not as much as the abusive behaviour of my employers.

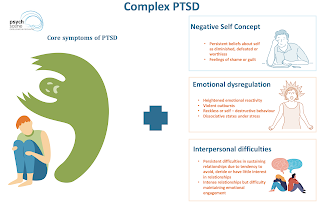

PTSD is a disease of memory. As Bessel van der Kolk observes in The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma, “traumatized people simultaneously remember too little and too much.” Sometimes trauma results in disassociation or repression, leaving no accessible memories at all. More often, trauma prevents key brain modules like the thalamus and hippocampus from integrating our experiences into “normal” memories. According to Dr. van der Kolk, “the imprints of traumatic experiences are organized not as coherent logical narratives but in fragmented sensory and emotional traces: images, sounds, and physical sensations.”

When I realized I had no memory of seeing Something Rotten! on Broadway in October 2015 – even Christian Borle’s Tony-winning portrayal of my idol Will Shakespeare – I went back to my collection of Playbills to figure what else was missing.

The only other show I saw on that trip was Fun Home, a musical based on lesbian cartoonist Alison Bechdel’s memoir about growing up in a repressed and dysfunctional environment (she was raised in her family’s funeral home). While Bechdel was away at college, her father killed himself rather than come out of the closet.

In contrast with Something Rotten, I remember seeing Fun Home on Broadway. I’ve also read Bechdel’s graphic memoir. But my memories of both are fragmentary.

|

| Theatre Under the Stars |

Early in his career, Sigmund Freud successfully treated hysteria patients who had PTSD-like symptoms. Freud reported his patients could not access traumatic memories because of the “severely paralyzing” effect of strong emotions like fright and shame. Freud concluded “the ultimate cause of hysteria is always the seduction of the child by an adult.”

However, as Bessel van der Kolk observes, when “faced with his own evidence of an epidemic of abuse in the best families of Vienna – one, he noted, that would implicate his own father – he quickly began to retreat.” Freud shifted his emphasis from real-world childhood trauma to “unconscious wishes and fantasies” like Oedipus complexes and penis envy. A century later, the leading psychiatry textbook in 1974 stated that “incest is extremely rare,” while opining it probably “allows for a better adjustment to the external world,” leaving “the vast majority” of underaged victims “none the worse for wear.”

Since then, we’ve learned PTSD is very real, and that it’s not just a soldier’s disease. Here is Dr. van der Kolk’s call to action in The Body Keeps the Score after four decades treating trauma victims: “Child abuse and neglect is the single most preventable cause of mental illness, the single most common cause of drug and alcohol abuse, and a significant contributor to leading causes of death such as diabetes, heart disease, cancer, stroke, and suicide.”

My childhood best friend Paul killed himself a few months after he was diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder. In a pioneering study by Dr. van der Kolk and his Harvard colleague Dr. Judith Herman, 81 percent of patients diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder also had histories of severe child abuse. On my way to see Something Rotten!, sitting in line at the Peace Arch border crossing, I read more details about the study in The Body Keeps the Score. And I remembered various odd things Paul said or did over the years. Suddenly I made the horrifying connection – my friend Paul likely endured abuse while we were in elementary school together.

|

| Christian Borle and "Will Power" on Broadway |

When I visited New York in October 2015, my PTSD diagnosis was still a few weeks away. But I was well on the way to rock bottom. Even after Theatre Under the Stars refreshed my recollection, I still can’t remember seeing Something Rotten!.

I can think of several explanations for the memory gap. The first is the general effect of my disability. As a wrote in “Better-ish,” although many of my fuzzy memories from that period finally snapped into place, others never did. Instead my brain concluded the simplest way to adjust my internal clock was to delete two years from the timeline. It was like switching to Daylight Savings Time. Or like when England converted from the Julian Calendar to the Gregorian Calendar, and eleven days were dropped from September 1752. Nevertheless, there’s a silver lining: I remember half as much Donald Trump presidency as everyone else.

Another possible explanation for erasing Something Rotten! is my obsessive relationship with Shakespeare. For example, the best class I took at Yale Law School was Hal Bloom’s graduate Shakespeare seminar. My bardolatry goes beyond ordinary English Major fervor. I was born exactly four hundred years after William Shakespeare. (To the day, after adjusting for the switch to Gregorian calendar). All my life, or at least from 1964 to 2015, I could easily compare myself to where Will was at a particular age: having his three kids in Stratford during the ’80s, writing classics like Hamlet in the ’90s, retiring to the country in the aughts, and dealing with poor health in the teens. Shakespeare died in 1616, on what would have been his 52nd birthday. On that date four hundred years later, senior managing lawyers at the Attorney General’s Office realized the State’s employment lawyers and their investigator had broken the law and discriminated against me. Rather than correct their errors, they hastily terminated my employment and embarked on the triggering coverup that continues today. My life stalled at age 51. As my health and career unraveled in 2015-16, I felt more doomed that Will Shakespeare. Now it feels like the clock has started again.

But there’s a third explanation for my memory blocking out Something Rotten!. As I sat in Malkin Bowl last month, I recognized some of the characters and plot developments from listening to the original cast album. For example, during Act I, Will Shakespeare’s rock-star narcissism was predictably charming. I was also prepared to see Nick Bottom weave his soothsayer’s misleading fragments of prophecy into the fiasco of Omelette: The Musical. (It’s no Springtime for Hitler, but it’s no Hamlet, either.) What surprised me was Shakespeare’s pathetic efforts during Act II to re-ignite own creative fire. Eventually Will is so desperate he steals Nigel Bottom’s brilliant draft script of Hamlet. After Omelette: The Musical bombs, Shakespeare conspires with the authorities to banish Nick, Nigel, their wives, and the soothsayer to America in order to cover up his own plagiarism.

Why did my memory block out the entire show, including the fact I saw it on Broadway? Because Something Rotten! centers on writer’s block. And finding your own voice. Which turns out to be how I finally worked my way through complex PTSD over the last few years. I still don’t remember anything from the first time I saw Something Rotten!. But I’m happy so many of the other rotten things from that time in my life are finally beginning to heal.

|

| Daniel Curalli as Will at Theatre Under The Stars |