As we inch towards a post-pandemic New Normal, the entire Vancouver Men’s Chorus is finally gathering to rehearse together again on Wednesday evenings. Our June show on Granville Island, “R-E-S-P-E-C-T,” will be a salute to women’s music. We started learning the same songs two years ago, before the coronavirus pandemic silenced choirs and closed the Canadian border for the first time since the War of 1812.

The week before the border closure, I was in Vancouver for VMC’s annual fundraiser “Singing Can Be a Drag.” I’ve never done drag myself. Instead, I was a volunteer usher.

In addition to avoiding high heels, prior to February 2020 I also had never lost consciousness. The last thing I remember about the drag show is the lights dimming at the beginning of the queens’ performance. I’m told I fainted and fell down the stairs backstage soon afterwards. As I wrote in “Falling Can be a Drag,” I still can't remember anything from the rest of the night, including the hot fireman who arrived to minister to me after someone called 9-1-1. (Inevitably, VMC President and uberextrovert Yogi Omar ended up with the medic’s telephone number.)

Back home in Bellingham the next day, I woke up feeling sore all over without knowing why. When I returned Yogi’s frantic “how are you feeling???” text, I discovered what happened the night before. So I drove across town to the walk-in clinic. After the nurses heard my story, they made me walk across the parking lot to the Emergency Room at Saint Joseph’s Hospital for an ECG and CT scan.

None of the tests revealed anything abnormal. My excellent physician Dr. Heuristic eventually concluded the episode was a stress-related manifestation of my disability, triggered by particularly intense emotional experiences.

A random convergence of legal, medical, family, and financial crises made the last few days my most stressful and triggering week ever.

On Wednesday I was in Vancouver on my way to chorus rehearsal when I lost consciousness for the second time in my life. However, instead of drag queens, this time I had the good or bad luck of fainting in front of a couple of nurses while visiting my brother on the spine floor at Vancouver General Hospital.

|

| Leishman Brothers: Brian (lung cancer survivor); Roger (PTSD); Warren (bald); Doug (spine cancer) |

My next younger brother Doug was diagnosed with spine cancer five years ago after back pain revealed an inoperable tumor. As the heaviest Leishman brother, Doug was defensive about failing to notice a grapefruit-sized lump in his pelvis: “They’re big bones!”

Despite many challenges, Doug is blessed with the best family in the world, marvelous medical providers, and Canada’s sane healthcare system. He was able to walk my eldest niece down the aisle at her wedding two summers ago. Since then, Doug has spent most of his time bed-ridden at home in British Columbia. This month he was airlifted to VGH for nine hours of emergency surgery after a growing neck tumor paralyzed his upper body. The surgery went well, and Doug is learning how live with a wheelchair.

Our family has observed numerous parallels and contrasts as my brother faced cancer at the same time as I was learning to live with mental illness on the other side of the border. Last Wednesday, I arrived late to visit Doug in the hospital after spending my morning writing a particularly stressful letter to the State’s lawyers in response to their continuing refusal to acknowledge that I have a disability. My stress was further exacerbated by the fact that the judge in my lawsuit against the Governor’s Office had scheduled an inevitably triggering hearing for Friday morning.

While visiting my brother’s hospital room and listening to a discussion of pain management, I became lightheaded and collapsed to the floor in front of two nurses. I thought it was just a low blood sugar moment. The nurses quickly placed me in a wheelchair and gave me apple juice. I was pale and clammy, with a slow heart rate, but still alert. Until yesterday, I’d never had an even slightly elevated blood pressure reading – I inherited my father’s high cholesterol, not my mother’s hypertension. However, one of the VGH staff said she had never before seen a blood pressure reading where both the numbers had three digits.

Other than losing consciousness in the wheelchair after they checked my vital signs, this time I remember the rest of the experience. Despite the melodramatic interruption, Doug said it was educational to watch me pass out. My sister-in-law told us I looked just like my brother when he overdoses on morphine.

There are both advantages and disadvantages to passing out in a hospital. Rather than attend chorus rehearsal, I spent Wednesday evening at Vancouver General being tested and observed.

Once I regained consciousness, one of my brother’s nurses insisted on wheeling me through a backstage maze to the ER waiting room. By the time she handed me over to the triage nurse my vital signs had all returned to normal. A technician wired me up for a quick ECG and assured me my heart looked fine.

At this point they took away my wheelchair and sent me back to the ER waiting room, where I found my efficient sister-in-law on the phone finding me a place to stay overnight. Then the nice Canadian nurses tricked us. They led me down a hall to finally get my insurance information, something that happens much earlier in the process in the States.

It could have been another triggering situation – trying to communicate about a stressful topic through a plexiglass screen while wearing masks. Fortunately, although English was not her first language, this was hardly the first time she had filled out the paperwork for an unfortunate American finding himself trapped in the province’s largest hospital.

“Trapped” is the right word. After I signed a bunch of forms without reading them, she led me alone through a new set of doors to the secret inner waiting room.

Someone politely drew a few vials of blood. I texted my sister-in-law and told her I’d been kidnapped. Then I found a chair in a waiting room filled with sniffling children, Asian grandmas, and moaning hockey players.

As I looked at my new surroundings, I took a picture of the sign above the chair directly across from me. It asked: “Do you struggle with opioid use?” Ironically, this is what the nurses were talking about in my brother’s hospital room when I fainted. As Doug says, the best thing about having cancer is that even in the middle of a fentanyl public health crisis you get as much morphine as you need. Too much, in fact.

Eventually I got a text back from my sister-in-law saying “Wrong number.” Apparently her contact information in my iPhone was out of date. Unfortunately, this was also the only phone number I’d given to the hospital staff.

Fortunately, I was finally able to reach my parents. They hadn’t answered my previous calls because they were busy driving my college freshman nephew to the ER in Bellingham. (He had a concussion. I still haven’t heard that story.) I tried to obtain my sister-in-law’s actual phone number from my mother without sounding too alarming.

As a single parent, I’ve already spent too many hours in waiting rooms with a dying iPhone battery and nothing to do, eat, write, or read. Eventually I got bored and blew up the photo I’d taken of the “Welcome to the VGH Emergency Department” poster:

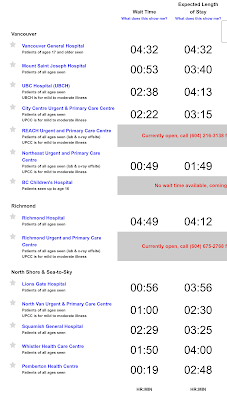

Modern technology is amazing. As directed by the poster on the wall, I clicked on the link “edwaittimes.ca” and discovered the current wait time for each emergency room in British Columbia. Unsurprisingly, Vancouver General Hospital has the largest and slowest casualty department in the province:

According to the website, I could expect to wait four hours and thirty-two minutes before getting my lab results and seeing a doctor. Perhaps coincidentally, I could expect to wait four hours and thirty-two minutes before escaping from VGH. I was almost halfway there.

Meanwhile, I hadn’t eaten for six hours. I could sense actual hypoglycemia on the horizon. VMC rehearsal was about to start without me. I was crabby. I’d left my library book, laptop, and phone charger in the car, which by now was illegally parked. My sister-in-law texted with an offer to bring me a snack from the hospital vending machines. I told her I’d been through enough triggering experiences for one Wednesday.

When I was tricked into walking across the parking lot from the Bellingham walk-in clinic to the Emergency Room two years ago, the American nurses promptly put me into a hideous hospital gown and hooked me up to a heart monitor. Armed guards surrounding the hospital campus prevented any thought of escape.

Everything is better in Canada. Despite my sister-in-law’s maternal sighs, I went AWOL. I used the last of my colorful foreign money to buy an invigorating milkshake and fries at Johnny Rocket’s. Then I moved my car to a nearby parking spot, grabbed my backpack, and snuck back into the ER treatment waiting room. No one noticed I was gone.

Drunk on chocolate milkshake and library books but completely sane and sober, eventually I decided it was time to drive home to my children.

After more than five hours had passed, I went to the nurses’ station to tell them I was invoking the Geneva Convention and returning to the States. They pulled up my chart and pointed out I hadn’t seen a doctor yet. I promised to turn myself in to my physician in Bellingham. I asked if my bloodwork had come back. The nurse said it looked fine.

After I self-helped myself to discharge from the ER, I found my way through the hospital maze back to the spine floor. My brother and sister-in-law were on the phone with my oldest niece and her wholesome BYU husband. Their baby is due this week. Last month her brother and his wholesome BYU wife passed them by producing the first great-grandchildren – identical twin boys. Despite the tragicomic plagues that beset us, my family is eternally blessed.

So far I’ve been to five Canadian province (British Columbia, Alberta, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia). How many states have I visited?

Business travel and multiple cross-country moves got me to the low forties. Then a decade ago I represented the Gay Softball World Series in a First Amendment case that involved deposing LGBT athletes across the nation. On just one trip I crossed off Arkansas, Mississippi, and Georgia. I also changed planes in Birmingham, but never left the airport. After my law school twenty-five year reunion in 2015, I rented a car and finally road tripped to Vermont, which brought me to forty-nine states. Fifty if you count Alabama.

In my first blog essay about our family’s devotion to the PeaceHealth walk-in clinic, “Dr. Practical,” this is what I presciently wrote:

I've managed to avoid hospitals for fifty-five years. In particular, as long as I retain any voluntary muscle function, I’m never going to be sick enough to go to an emergency room. Fortunately, being surrounding by loving family means that if I really needed medical assistance, someone will take me to the ER as soon as I lose consciousness. Then the ER stops being an indefensibly profligate expense.

Six months later, a gaggle of Canadian drag queens pushed me down the stairs. The next morning the nurses at the walk-in clinic tricked me into walking across the parking lot to the Emergency Room to get my heart and brain examined. At the American ER, they stripped me and tied me to a hospital bed.

This week the Canadian nurses were much nicer. Still, they were the ones who wheeled me to the ER after I lost consciousness, with my brother and sister-in-law egging them on. If that counts as “going to an emergency room,” then I’ve also been to Alabama and get to cross off all 50 states.