My brother Doug Leishman died on April 25, 2023 after enduring spine cancer for the last six years. Doug asked that each of his brothers speak at his memorial. This is what I shared at the Mormon church in Bellingham on May 16, 2023.

I’m grateful for this opportunity to meet together as Doug’s family and friends. Gatherings of our extended family always have one very obvious impact on me and many other Leishmans, including Doug. After listening to everyone’s stories, I forget how to pronounce my own last name. It will take several days to switch back from Lishman to Leashman.

Leishman is an ancient Scottish surname. It’s been pronounced the same way for hundreds of years, since before Shakespeare and the King James Bible. But our branch of the family met the Mormon missionaries in Scotland during the 1850s. They sailed across the ocean and walked across the prairie. When they reached Utah, Brigham Young sent them north to settle Wellsville, in Cache Valley. They became a peculiar people, and developed a peculiar dialect. “Roof” became “ruff.” “Creek” became “crick.” And “Leishman” became “Lishman.” That’s how my brothers and I grew up pronouncing our last name.

When I began my professional career, I made a conscious choice to introduce myself as “Roger Leishman.” Just like I don’t say “crick.” But we don’t make a big deal about pronunciation, and respond politely to anyone regardless of how they say our name. Except for “Leischman,” of course.

Like Doug, on days like today we are all “Lishmans.”

.jpg)

When Kyla posted the announcement on Facebook letting folks know Doug had died, I was moved by the outpouring of comments. Three or four repeated words stood out: “Nerd.” “Smart.” And “funny.” I realized that’s what the comments would say for all four Leishman brothers.

Folks often remark on how much we resemble each other and both our parents, but they struggle to put their finger on the specific similarity. Folks would say we are even more similar in our personalities. Especially my sisters-in-law, and our children.

There are differences. Yes, we’re all nerds, but Doug is the Dungeons & Dragons nerd. We’re all funny – but Doug is the master of sarcasm.

.jpg)

On the wall at my parent’s house there is a framed series of pictures of the four Leishman Brothers. The same series of photos hangs on the wall in my living room. They were taken a few years ago near Lake Whatcom. It was the only time when the brothers, parents, and grandchildren were all in the same place at the same time. So we hired a photographer.

There are four pictures in this series. In the first picture Roger, Doug, Brian, and Warren are all smiling appropriately for the camera.

In the second picture, Doug has a quiet grin. He is sticking his finger into Warren’s ear.

In the third picture, Warren has his finger in my ear, and everyone is grinning.

In the fourth picture, the brothers have all burst into laughter.

If you look close, you can see differences between the Leishman Brothers. Warren went bald early. I’ll always be the oldest, and the gay one. And as Brian is quick to point out, he is the tallest brother.

A couple of months ago, I had the opportunity to drive to Kamloops with my parents. Doug looked about the same as the last time I’d visited: lying in a hospital bed on his stomach in the corner of the living room, surrounded by his children and grandchildren. Before we drove back to Bellingham, I reached in for a goodbye hug. I was struck by how thick and curly Doug’s hair had gotten. And still so dark.

Technically, I am now the least bald Leishman brother, and Warren is the least grey. But I think we should retire the hair titles with Doug as champion.

.jpg)

Gatherings like this are important because we can help each other remember the real Doug.

I often find it a challenge to recall stories from the past without a picture or something to remind me. Faces are especially hard. Last month when my parents called to let me know Doug had died, I lay in bed weeping because I couldn’t remember what Doug looked like before cancer.

Doug spent the last few years of his life being seen from a strange angle. Spine cancer prevented him from walking or lying on his back, so we only saw him lying on his stomach. That’s how I noticed his dark curly hair.

I knew if I got out of bed and walk into the living room, the pictures on the wall would help me remember laughing together with Doug. But I wanted to conjure the memories on my own. Eventually I was blessed to remember two images of the real Doug.

The first memory was from the spine floor at Vancouver General Hospital. A year and a half ago, Doug was paralyzed by a new tumor in his neck. He was airlifted from Kamloops to Vancouver, where two separate teams of surgeons worked from both front and back, removing the cancer and reconstructing his vertebrae. Doug spent the next hundred days at VGH.

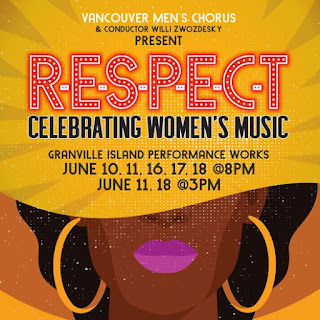

I sing in Vancouver Men’s Chorus, which rehearses on Wednesday evenings. Each week I would drive up early and spend time in Doug’s room. He was propped up on his back in a hospital bed. It’s the only time in the last few years when I got to look Doug in the face. It also gave me the opportunity to sit down and spend hours talking with my brother, sometimes with other family and sometimes just the two of us.

We discussed our challenges living with cancer and with PTSD. But mostly I remember sitting together face to face with Doug, and talking about what it means to be a father.

Spine cancer targets the parts of the body that signal pain. In addition to dealing with Doug’s underlying symptoms, his healthcare team always focused on making him comfortable. Greedy pharmaceutical companies and irresponsible doctors have created the terrible opioid epidemic that is ravaging our communities. But modern opioids are also miracle drugs that make it possible to endure to the end.

While Doug was at Vancouver General, three separate teams were responsible for the opioids in his IV drip, his pillbox, and the little pump installed in his chest. I happened to be visiting the hospital when the pain management teams realized not only were they not communicating clearly with each other, but they were using three incompatible measurements to track dosages. One team would give Doug enough medicine for him to sit up all the way for a meal. After a few minutes they would have to crank the bed back down for him to rest, which would react with the medicine from the other teams. Sometimes Doug would overdose. And then they would start over.

While visiting the hospital, I also observed the laborious process of putting Doug in a wheelchair. I listened to presentations about grueling rehabilitation programs at inconveniently located facilities.

After more than three months at VGH, Doug was finally stable enough to leave the spine floor and return home. When I visited Kamloops with my parents a few months later, there was no sign of the elaborate rehabilitation programs we’d heard about at the hospital. Instead, Doug used every ounce of his energy to spend as much time as possible with his family. His world was tiny: a bed in a corner of a living room. But Doug’s world was as large as eternity because he was at the center of his family.

As I lay in bed last month grieving, I remembered a second image of Doug, from a couple of summers ago. It was the height of the pandemic. Nothing was harder for our family than the Canadian border being closed for the first time since the War of 1812. Doug was stuck in a bed in Kamloops, and my parents and I were stuck in the States.

Like everything else, the Mormon temples closed. But by a miraculous convergence of circumstances, Katie and Christian were able to get married in my parents’ backyard in the strangest Mormon wedding ever. I will always remember the last time I ever saw Doug walking: he staggered down the aisle, holding on to his daughter, the happiest man and the proudest father in the world.

Besides “nerd,” “smart,” and “funny,” the other words Doug’s friends repeatedly used to describe him on Facebook were “family” and “father.” Fatherhood is at the center of all my brother’s lives. That is the great gift our parents and now Doug and Kyla have given to each of the “Lishmans.”

Church policies and meeting schedules come and go, but the fundamentals are eternal, like the familiar slogan “Families are forever.” I recognize “forever” is way too long for some families. But not for us.

When I was young, the president of the church was David O. McKay. He delivered a similar message, but with more words in it: “No other success can compensate for failure in the home.” (It was the Mad Man era – our ad slogans were longer than my kids’ generation, just like our attention spans.)

My brother Doug lived a successful life when it comes to what really matters. I hope we can all remember and be inspired by Doug’s example.

Douglas Todd Leishman

1967-2023

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)