We live next door to Washington’s third largest university. Unsurprisingly, on our walks Bear and I frequently encounter nerds.

The other day we ran into a young man on campus in obvious need of a dog fix. As he gave Bear a glorious tummy rub, the student exclaimed “He has heterochromia!” That’s an impressive nerd word – Bear was indeed born with two different colored eyes. My kids picked Bear out of the litter because of his soulful blue eye and his earnest brown eye.

After the Western student finally tore himself away from his canine cuddle, he asked whether Bear is an Aussiedoodle. Another remarkable nerd display. When I ask how he guessed the correct breed, he said it was because he observed Bear exploring the world.

|

| Heterochromia is less noticeable with Tina Turner bangs |

In her book Animals Make Us Human, autistic animal husbandry expert Temple Grandin reminds us humans are animals too, with brains that evolved over millions of years. Grandin uses the model of brain function described by neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp four decades ago in his research on the neural bases of emotion. Panksepp identified seven primal emotions. Grandin follows Panksepp’s custom of labeling each in allcaps: CARE, FEAR, LUST, PANIC, PLAY, RAGE, and SEEKING.

CARE is the emotion underlying parental love. LUST fuels sex and sexual desire. PANIC (or GRIEF) signals distress to an animal’s “social attachment system,” and “probably evolved from physical pain.” The separate emotion of RAGE evolved from animals’ experience of being captured and held immobile by a predator. According to Grandin, “frustration is a mild form of RAGE that is sparked by mental restraint when you can’t do something you’re trying to do.”

In contrast with PANIC and RAGE, the core emotion PLAY “produces feelings of joy.” As I wrote in “PLAY On!,” the same neural pathways that inspire Bear and Buster to boisterously frolic at the off-leash park became the foundation for quintessentially human urges like art and music. All seven of Panksepp’s categories represent very human emotions whose effects can also be observed in other animals.

In Panksepp’s model of animal brain evolution, SEEKING is the core emotion associated with curiosity and novelty. It’s the aspect of Bear’s Australian shepherd heritage that drives him to explore the world.

An animal’s SEEKING impulse may be in tension with FEAR, another primal emotion that is necessary for survival in a dangerous and mysterious world. According to Grandin, “at least a portion of the healthy amygdala acts as if it has an anxiety disorder – searching for threat in response to uncertainty…. The single most important factor determining whether a new thing is more interesting than scary is whether the animal has control over whether to approach the subject.”

Grandin suggests FEAR and SEEKING “may operate like different-sized weights put on the opposite ends of a balance scale.” I agree that personality statistics for human or animal populations would probably show an inverse correlation between curiosity and dread. Nevertheless, FEAR and SEEKING represent separate emotional drives. For example, Buster is much too dim-witted for sophisticated FEAR or SEEKING behavior. (Instead, Buster is a bundle of the tics and awkwardness associated with PANIC disorders.) Buster invariably leaps out of the car into traffic, yet seldom strays far from his human monitor.

In contrast, Bear is smart enough to balance both caution and curiosity.

Last year I read several excellent books about how our brains process probabilities, choices, disappointment, and uncertainty. My upcoming blog essay “How Lucky Can You Get?” dives into these topics, including some of the insights from my favourite book of 2021, What are the Chances? Why We Believe in Luck, by neuroscientist and statistician Barbara Blatchley. According to Blatchley,

Luck is the way you face the randomness in the world. If we are open to it, accepting, not anxious or afraid, willing to learn from mistakes and to change a losing game, we can benefit from randomness. We can gain a modicum of control over this aspect of life, even if we can't control the universe on a large scale. Randomness will happen no matter what we do—chaos theory rules in our universe. Knowing how to roll with the punches; now that's lucky.

Blatchley analyzes four kinds of luck originally identified by Zen Buddhist neurologist James Austin in his 1978 book Chase, Chance, and Creativity: The Lucky Art of Novelty. Dr. Austin’s first type of luck occurs by pure chance. Type I or blind luck is “random and accidental; it occurs through no effort of our own and against all odds.”

In contrast with Type I luck, Dr. Austin’s second type of chance, “luck in motion,” is exemplified by Bear’s SEEKING attitude. According to Dr. Austin, Type II luck “favors those who have a persistent curiosity about many things coupled with an energetic willingness to experiment and explore.”

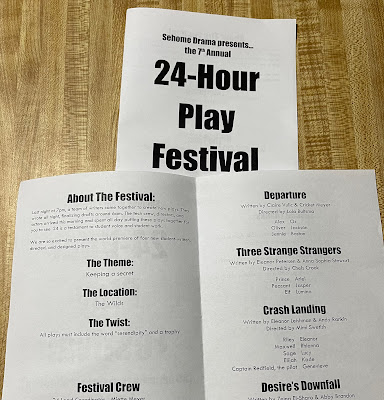

Last month Sehome High School put on its annual “24-Hour Play Festival.” On Friday night at 7 pm, four teams of writers arrived at the school to create new one-act plays overnight. The playwrights were assigned the same theme – “Keeping a secret” – and the same location – “The Wilds.” At midnight the producers added a random twist: “All plays must include the word serendipity and a trophy.”

The tech crew, directors, and actors arrived Saturday morning and spent all day putting the four plays together before performing them Saturday evening. Eleanor was both a writer and an actor, which meant she stayed up for 46 hours straight. Their play “Crash Landing” presented a Lost-style jungle island mystery.

“Serendip” is the ancient Sanskrit name of the island of Sri Lanka. The English word “serendipity” first appeared in a 1754 letter by novelist Horace Walpole, and referred to a Persian fairy tale, The Three Princes of Serendip. According to Walpole, the three princes were “always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things which they were not in quest of.” They deserved trophies for their discoveries.

That’s the difference between serendipity and mere fortuity: it is precisely because the Princes of Serendip were on a quest for something that they found something else.

“Bear, you are just like my father. And me.”

My Apple Watch transcribes my dialogues with Bear as we walk. That recent quotation came as Bear sniffed his way along the trail from the off-leash park to the beach. Bear enjoys playing catch and frolicking at the park. But soon it’s time to move on.

My father turned 82 last month. He regularly golfs, bowls on multiple teams, and plays bridge several times a week. Dad is endlessly curious, and always busy with something. I’ve never understood the attraction of golf, the alleged sport that is often described as “a good walk spoiled.” I don’t need a pretext to be outdoors. I can just go for an unspoiled walk. But like my father and Bear, I have to keep going.

In the Mormon church, the children’s program is called “Primary.” When I was growing up, “Blazers” was the class for the oldest boys, just before turning twelve and graduating to Boy Scouts. You earned a glass medallion for your personal Blazer banner by memorizing and reciting each of the thirteen Articles of Faith, which are like a catechism of Mormons’ most basic beliefs. Obviously I had to earn every one. The most coveted medallion was for memorizing the Thirteenth Article of Faith, which was much longer than the other twelve.

In 1976, I was the only boy in our class who could make it by memory all the way to the end of the Thirteen Article of Faith. I still can. It happens to be what I believe:

We believe in being honest, true,

chaste, benevolent, virtuous,

and in doing good to all men;

indeed, we may say that we follow

the admonition of Paul—

We believe all things,

we hope all things,

we have endured many things,

and hope to be able to endure all things.

If there is anything virtuous,

lovely, or of good report or praiseworthy,

we seek after these things.

Serendipity is the process of looking for something and finding something else. Nevertheless, what you’re seeking matters.

|

| Calligraphy by 1980s Roger for the family room at his parents' house |

No comments:

Post a Comment