Humans have a deep need to make sense of their experiences. We accomplish this by telling stories to ourselves and each other.

It’s biological. According to Nobel prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman, “The normal state of your mind is that you have intuitive feelings and opinions about almost everything that comes your way.” As new sensory input is added to our existing memories and beliefs, human brains constantly strive to maintain a coherent model of the world around us.

Even though we seldom have access to every piece of relevant information, life has to go on. Our brains are therefore designed to make sense of things that don’t necessarily make sense yet, by telling stories anyway.

Human brains consist of two hemispheres. No one knows why. The famous “left brain” and “right brain” are connected by a thick bundle of nerve fibers, like an industrial extension cord, called the corpus callosum.

Even with the recent development of imaging technologies like MRI, CT, and PET scans, most aspects of brain function remain a mystery. However, previous generations had even less data, particularly regarding healthy brains. Scientists had to rely either on autopsies or on their observation of patients with localized brain injuries.

During the 1960s and 1970s, before the advent of powerful new medications, some epilepsy patients with overwhelming symptoms were treated by severing their corpus callosum. This stopped the electrical firestorms in their brains. But it also radically altered how the patients’ minds worked.

Eminent neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga has spent his career tracking this cohort of patients to see what their experiences teach us about how the human brain processes information from each hemisphere. Here’s Steven Pinker’s description of one of Gazzaniga’s famous experiments:

Language circuitry is in the left hemisphere, and the left half of the visual field is registered in the isolated right hemisphere, so the part of the split-brain person that can talk is unaware of the left half of his world. The right hemisphere is still active, though, and can carry out simple commands presented in the left visual field, like “Walk” or “Laugh.” When the patient (actually, the patient’s left hemisphere) is asked why he walked out (which we know was a response to the command to the right hemisphere), he ingenuously replies, “To get a Coke.” When asked why he is laughing, he says, “You guys come up and test us every month. What a way to make a living!”

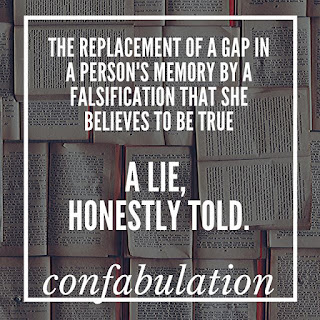

In The Happiness Hypothesis, philosopher Jonathan Haidt uses the word “confabulation” for the phenomenon Gazzaniga observed: even people with healthy brains “readily fabricate reasons to explain their own behavior.”

In a technical psychological sense, “confabulation” is pathological. German psychiatrist Karl Bonhoeffer coined the term in 1900. He used it to describe when a person gives false answers, or answers that sound fantastical or made up. Confabulation is a common symptom of various disorders in which made-up stories fill gaps in memory.

Haidt uses the metaphor of a “press secretary” to explain the role of the reasoning module of our brain and its relationship to our conscious mind. We can’t resist offering explanations, even when our brains are operating with incomplete information.

Haidt wrote his book long before Donald Trump’s election. Sarah Huckabee Sanders may have removed any distinction between the confabulation of actual press secretaries and the behavior of pathological liars.

Lawyerly confabulation can also be pathological.

When I began seeking answers and accountability three years ago, the Washington Attorney designated Assistant Attorney General Suzanne LiaBraaten to represent the State’s interests in

connection with my disputes. Although other lawyers from the Attorney General’s Office have subsequently appeared, including Solicitor General Noah Purcell, Ms. LiaBraaten has remained the State’s point person. She should be very familiar with the record by now.

In December 2018, I filed bar complaints regarding the conduct of the two experienced employment lawyers who were involved in violating Rule of Professional Conduct 4.2, which prohibits lawyers taking advantage of a person who is represented by counsel by having him interrogated without his lawyer’s knowledge. These bar complaints are currently pending with investigators at the Office of Disciplinary Counsel of the Washington State Bar Association.

On January 18, 2019, Ms. LiaBraaten filed a written “Preliminary Response” to the bar complaints on behalf of her colleagues Chief Deputy Attorney General Shane Esquibel and his flunky Assistant Attorney General Kari Hanson. Among other misleading and inaccurate statements in the Preliminary Response, Ms. LiaBraaten made the following assertion:

“While Mr. Leishman was on home assignment based upon his alleged misconduct, the reasonable accommodation process was put on hold.”

However, an employer cannot unilaterally place “on hold” the interactive disability reasonable accommodation process required by the Washington Law Against Discrimination and the Americans with Disabilities Act. To the contrary, employers have an independent affirmative duty to participate in good faith in an interactive reasonable accommodation process. See, e.g., Frisino v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1, 160 Wn. App. 765, 779-80, 249 P.3d 1044 (2011) (“reasonable accommodation envisions an exchange between employer and employee”). Ms. LiaBraaten’s representation was false.

Last year I submitted a request to the Attorney General’s Office under the Public Records Act seeking a copy of “All records showing that the reasonable accommodation process was placed on hold while I was on home assignment.” Over the next five months, the Attorney General’s Office repeatedly requested additional time to respond. The Attorney General's staff referred to the purported “intricacies” of my PRA request, and represented that personnel in the office were diligently engaged in efforts to locate responsive documents, if any.

However, when they finally responded, Ms. LiaBraaten’s colleagues at the Attorney General’s Office were unable to identify a single responsive record. The State’s failure to locate any corroborating evidence comes as no surprise – it’s impossible to escape the conclusion that Ms. LiaBraaten manufactured her post-hoc rationalizations out of whole cloth, presumably for the purpose of deceiving the Office of Disciplinary Counsel about her co-workers’ misconduct.

However, when they finally responded, Ms. LiaBraaten’s colleagues at the Attorney General’s Office were unable to identify a single responsive record. The State’s failure to locate any corroborating evidence comes as no surprise – it’s impossible to escape the conclusion that Ms. LiaBraaten manufactured her post-hoc rationalizations out of whole cloth, presumably for the purpose of deceiving the Office of Disciplinary Counsel about her co-workers’ misconduct.

As usual, last night after rehearsal with Vancouver Men’s Chorus I went out to the piano bar to listen to showtunes and sing along. It was the first anniversary of the weekly Showtunes Night at its current venue, so the crowd was large and in excellent voice. Several talented soloists took the mic – not me, obviously – and wowed the crowd. In the best performance I heard all night, one of the regulars sang “For Forever” from Dear Evan Hansen.

Like much of theater from Aristophanes through Shakespeare, the plot of Dear Evan Hansen centers on a misunderstanding. Evan is a high school social misfit. Conner, the older brother of Evan’s secret crush, is a troubled stoner. After Connor’s suicide, his parents erroneously leap to the conclusion that Evan and Connor had been close friends. For example, Connor was the only person at school who signed the cast on Evan’s broken arm. Connor’s distraught parents invite Evan over for dinner in hopes of making a connection to their son that they failed to achieve when he was alive.

“For Forever” is a lovely piece of music, and Patrick sang it exceptionally well last night. But for me it represents the worst moment in the play. Previously, Evan had responded to inquiries from Connor’s mother with vague nods that offered her some of the comfort she desperately needed. Then as Evan starts singing “For Forever,” he tells an elaborate story about breaking his arm while climbing a tree on an imagined idyllic roadtrip with his best bud Connor. The song’s fantasy also re-writes the reality that Evan actually broke his arm in a failed suicide attempt.

Evan is human. He can’t resist confabulating his casual acquaintance with Connor into a deeply meaningful friendship. Sure enough, once the previously isolated Evan starts weaving this increasingly detailed story, it brings him the attention and community he’d never known before. Connor’s sister becomes Evan’s girlfriend.

By the end of the play it all unravels. Of course.

I’ve written in previous blog essays like "Lilies That Fester" and "Some Days We Are All Less Smart" about how lawyers can easily enter into an unhealthy relationship with the truth. As I wrote last year about Ms. LiaBraaten herself in "7-Eleven Law School is accredited!,"

Being a lawyer is a moral hazard. There's always a tension between our duty of “vigorous advocacy” on behalf of the client, and our duty of “candor to the tribunal.” Everyone recognizes there can be grey areas. But not as much grey as some lawyers delude themselves into seeing.

I’m a big believer in second chances. (And third chances, and fourth chances, and….) Over the last year I repeatedly urged Ms. LiaBraaten to correct the false statements in her submission to the bar association. However, like her colleagues at the Attorney General’s Office, Ms. LiaBraaten refuses to acknowledge even the possibility of wrongdoing by anyone who has ever worked for the State, other than me.

Washington Rule of Professional Conduct 8.1(a) provides that a lawyer shall not “knowingly make a false statement of material fact” in connection with any “disciplinary matter involving a legal practitioner.” On February 11, 2020, I filed a complaint with the Washington State Bar Association regarding Ms. LiaBraaten’s misconduct.

When does your version of events stop being storytelling, and become a plain old lie? When you know it’s not true, but you keep telling same old story anyway.

No comments:

Post a Comment